I’ve been back trawling through the rich veins of Trove once again, trying to piece together whatever networks of wireless experimenters and entrepreneurs existed in the years roughly between 1895 and 1920 in the years before broadcasting took off.

As starting points I’m using names associated with the establishment of the Wireless Institute of Australia, or early wireless enterprises such as Father Shaw’s Maritime Wireless Company.

One person present at the inaugural meeting to establish the WIA in March 1910 was ‘Major Fitzmaurice’. Searching Trove with Fitzmaurice AND “wireless expert” yielded a brilliant article ‘A Night in an Airship” that appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald on 16 November 1912 about a military exercise that took place in England the previous month. A Naval Lieutenant named Fitzmaurice is wireless operator and one of the party that didn’t mean to spend an evening aloft. I’m unsure how he relates to the WIA Fitzmaurice, but I am sure it’s a great read.

Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 16 November 1912, page 7

A NIGHT IN AN AIRSHIP.

(BY LIEUT.-COL. EVERETT, 6th AUST. L. H.)

The 1912 manoeuvres will always be remembered as the first of their kind in which the commander of an army could use aircraft as a reliable and systematic means of obtaining information of the enemy’s movements. Aircraft have been used in manoeuvres for two or three years, but the results previous to this showed little more than the future possibilities of what is now known as the fifth arm. One must, however, bear in mind the important fact that in the manoeuvres aircraft were given a free passage into the enemy’s country, which in war, except against savages, as in Tripoli, they certainly will not have. How the aviators will make good their ground is a matter for much thought and conjecture, and difficult to practice in peacetime. Possibly the war in the Near East may teach us something.

But this article is not a treatise on the use of aircraft in war so much as an account of an all-night trip in H.M.A. Gamma, an unlooked for experience to those who took part in it, but one full of interest.

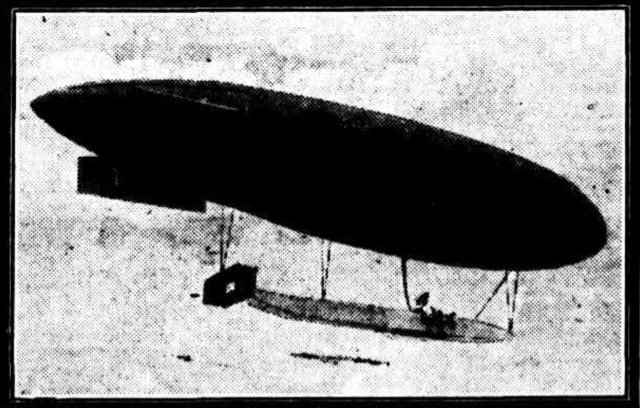

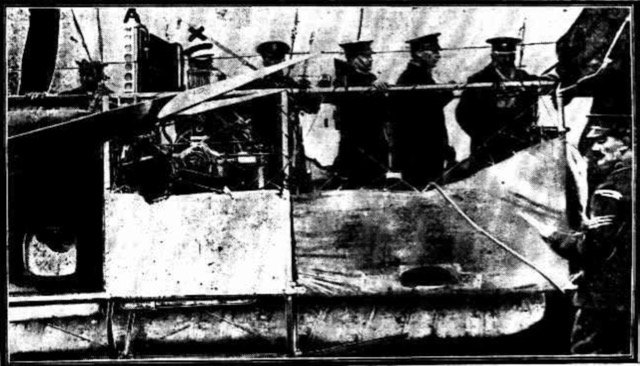

The picture of Gamma is worth studying before going further. The big egg-shaped balloon, or envelope as it is called, contains 100,000 cubic feet of hydrogen gas, and lifts a weight equal to 7000lb. Coal gas, which is generally used in ordinary spherical balloons seen at Hurllngham, is from one-third to one-sixth the cost of hydrogen, but has only half its lifting power or buoyancy. The bow of the ship is the end which has no covering over the frame. It is between the propellers and the open frameworks (see picture 2) that the pilot and crew stand or occasionally, very occasionally, sit. The wireless operator has his instruments behind the engines and propellers. The crew of the Gamma is from six to eight or nine, and consists of the pilot, who commands and navigates the ship, steersman; observer, who with his eyes glued on the map all the time directs the steersman, engineer, wireless operator, and logkeeper. When on manoeuvres a second observer is carried, and it is also well to have a spare hand to take messages to the operator, relieve either steersman or observer, move ballast about, and so on. The steersman is given a general direction by compass, but, especially with a beam wind or a wind on the quarter, the ship makes too much leeway for a true course to be kept, and towns, railways, and roads are identified on the map, and steered by.

When one becomes used to observing from a height it is wonderful how well objects can be seen, and, on a clear day, at even 4000 feet the number of men in a cavalry brigade, also guns and waggons can be identified and counted accurately and their pace estimated. This is by naked eye, and we found it almost impossible to use field-glasses, owing, we supposed, to the vibration. I mention 4000 feet, because it is at this height airships are supposed to be safe from artillery and rifle fire; aeroplanes are safe at about a height of 2000 feet from the ground. It is interesting to note that the Germans consider the value of airships for military purposes over aeroplanes is as 16 to 1. One of the advantages an air-ship has over an aeroplane is that wireless messages can be sent back the moment an observation is made, whereas the aeroplane has to return to its base to deliver a message.

Possibly wireless will be used before long on aeroplanes, which will much increase their usefulness, but the airship will still be an important factor in war; it can hover over ground for an indefinite time; can annoy the enemy by dropping bombs on him, and, perhaps, more important than all, it can watch him at night, a job very difficult if not impossible, to aeroplanes.

The “Gamma” had worked well all through manoeuvres, our wireless messages had been received without a hitch, and given valuable information, and there remained to us, we thought, only a night reconnaissance in which we hoped to locate the enemy’s bivouacs before daybreak on the morning of September 19, when it was, we understood, that the big battle would take place which would bring the manoeuvres to an end. We had orders to sail at 2.30 o’clock on that morning, but in the middle of our preparations on the previous evening, news was received that the manoeuvres had come to an abrupt termination, and we could pack up and go home on the following morning. To say that we were disgusted is only putting it mildly, but night reconnaissance being an important factor of our training, the opportunity of going out for even a couple of hours could not be lost. It was decided to make a demonstration over Cambridge, a distance of only 12 miles, leaving at 9.30 p.m., returning about 11 p.m.; orders were issued accordingly.

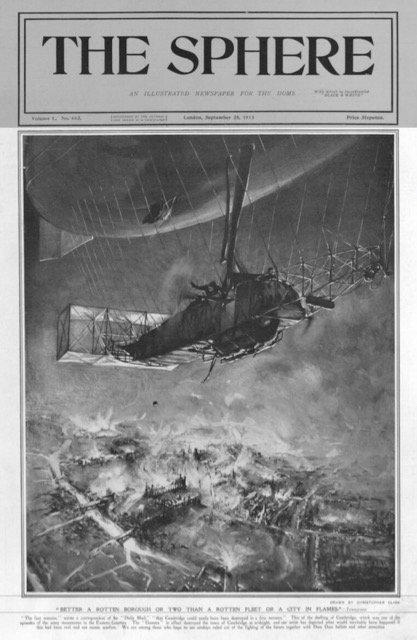

There was a north-east wind for us to beat against, dead in our teeth, in fact, and if it was going to be stronger up above than it was on the ground, which, in all probability, it would be, we expected a bad passage. Our expectations were realised and it was midnight when we arrived over Cambridge, and fired our rockets or imitation bombs. The “Shelling of Cambridge,” as the “Sphere” calls it, is well illustrated in the issue of that paper of September 23.

“BETTER A ROTTEN BOROUGH OR TWO THAN A ROTTEN FLEET OR A CITY IN FLAMES.” Tennyson “The fact remains,” wrote a correspondent of the “Daily Mail,” “that Cambridge could easily have been destroyed in a few minutes.” This of the shelling of Cambridge, which was one of the episodes of the army manoeuvres in the Eastern Counties. The “Gamma” in effect destroyed the town of Cambridge at midnight, and our artist has depicted what would inevitably have happened if this had been real and not mimic warfare. We are among those who hope to see airships ruled out of the fighting of the future together with Dum Dum bullets and other atrocities.

Very’s lights fired out of a 4-bore pistol, were the “bombs;” one of these would show up an infantry battalion in bivouac, but they have not a larger range than that. The navy use them at night for boat attacks. An airship is highly inflammable, both from the petrol fumes from the engines and the leakage of the hydrogen gas which escapes from the envelope, so the pistols had to be fired well in rear of the ship, and as low as possible. Even then, when the pistol was fired, the sparks flew about in rather an alarming way.

It was nearly 12.30 when we left Cambridge for camp, bowling along, with the wind behind us, at about 50 miles an hour; the searchlight in camp was to guide us home. We had been experimenting with a new one, a combination of hydrogen and acetylene gas, but only one small tube of each had been sent and the operator was afraid to keep it burning too long for fear it would fail when we were landing, and required it most. Three headlights from motor cars were kept burning near the camp, and the searchlight was ready as soon as the ship was seen or heard, but our camp near Kneesworth village was in a small field protected on the north and west sides by high trees, and completely hidden from the view of anyone approaching from that direction. The wind on our quarter sent us just far enough from our course to get us out of earshot or sight of the camp, but had the searchlight been used we would have had no difficulty.

To be lost in an airship at 1.0 a.m. at a height of about 2000 feet, and at least four hours before a landing could be attempted with any safety, was an experience new to even the oldest aeronaut amongst us. There was no moon; it was pitch dark, and only the twinkling lights of towns and villages far below showed us where the ground was. To try landing under these circumstances with no landing party to take the trail ropes and in a strong wind would possibly, if not probably, mean a smash, the details of which would be left to the imagination of the people who picked up the bits.

The engines were stopped, and a general overhaul made of ballast, petrol, and oil. There were 12 bags of ballast, each weighing 40lb, petrol for six hours, but only enough lubricating oil for half an hour, or, by using only one of the engines, an hour. We had been running both engines full out for 3½ hours. It is barely daylight by 5.0 a.m., and in the month of September often a dense fog for an hour or two after that; the engines had to be reserved for landing and emergencies. The higher one goes the lighter the atmosphere becomes, and consequently the greater pressure is given the gas in the envelope. When the ship sails, ballast is thrown out or added to make her just balance or lift slightly, so that any more ballast thrown out sends her up. At between 2000 and 3000 feet, if we could keep her at that, our gas pressure was easily maintained, and our pilot, Major Maitland, thought we had enough ballast to see us through.

The logkeeper on an airship makes an entry every five minutes, or more often if anything of special note occurs. The time and locality of the ship are noted, or rather, the locality over which the ship is passing, height, temperature, direction, and strength of wind, gas pressure, number of revolutions of the engine per minute, and the pace the ship is passing through the air. There are delicate instruments placed on a board on the side of the ship, which accurately record all these particulars. It was opposite this board, lighted by an electric torch, that the pilot placed himself and there remained until break of day, four hours later.

As I said before, we had to keep up to over 2000 feet to maintain our pressure; we were well up when we started drifting, and it was only a matter of handfuls of sand to keep us there “Four handfuls, six handfuls” came the pilot’s voice, then, when the wet sand or earth, with which the bags were filled was caked and hard to get out – “smart now” – Lieutenant Boothby, R.N., who doled out the precious stuff for those long hours, had his nails worn down and fingertips skinned long before his job was finished. The rest of the crew had not much to do, except pass up ballast bags and try to locate our position. Every change in temperature, and the temperature continually varies, affects the gas pressure, and in addition to that, down currents of air, and things terrestrial, such as woods and water draw the ship down; she came down quickly, and recovered slowly; progress downwards must be arrested at once. If the exact amount of ballast to do this could be gauged, so as to bring her back to the required height and only that height, the ballast thrower would not have been kept so busy, but it is impossible to hit it off every time or even often and when she shoots up, and gets too much pressure, the gas valve opens automatically, and before it closes again, which it does slowly and apparently reluctantly, a good deal of height is lost, and again ballast has to be thrown out.

We are drifting before the wind at the rate of about 20 miles an hour; many hundreds of lights were always in view, some in small clusters, indicating villages, then the long strings of a town’s lights would be seen and passed. The green and red signal lamps could be distinguished along the railways; heavily laden goods trains puffed slowly along the lines, now free from passenger traffic.

As daylight approached, and the supply of ballast was giving out, all things movable were collected; tools, spare tins of petrol, anything and everything which had any weight, even to the accumulators and dynamos, used for the wireless apparatus were got ready to throw out. This last item was almost too much for the wireless operator who sat over his property determined that only in the last extremity would he let his instruments be sacrificed. With the first sign of daybreak, we found the ground obscured by a thick fog, but this was soon blown away. There was a coating of ice round the carburetter, and much winding and coaxing were required to start the engine. One bag of ballast, the tools and wireless man’s gear were still in hand, when the port engine was started, but, owing to a leak in a water joint, it soon ran hot, and had to be stopped. However, some air had been pumped into the balloonettes, and made the envelope tight, so the little time taken in getting the starboard engine going, did not trouble us.

The elevator, which is a square frame work seen at the extreme rear of the ship in picture 2, was off, having been broken in an accident during the manoeuvres, and it was difficult to trim the ship. Our ballast had been carefully stacked to correct this, but now that it was all gone she dipped badly in the bows, which made her hard to steer, and running with only one engine accentuated this trouble. We tried to find a good landing place near habitations, and in a place sheltered from the wind, the first of these considerations being in the hope of getting some help. Some rising ground fringed by a wood and a line of high elm trees seemed to be a favourable spot, and the propeller was set to drive her down. However, a strong gust of wind caught us when we were near the ground, and it was seen, when almost too late, that it would be impossible to stop the way on the ship before she crashed into the timber.

The engine, which had been stopped, was started up full speed, and the propeller turned to lift us. Lieut. Osborne, R.N., who was steering, had to decide on either trying to squeeze through a gap between two trees (we had not time to rise over them) or put the helm hard over and chance her answering quickly to it and getting round. He decided on the latter course. With rudder to port, and the starboard engine helping us, we just grazed past the wood. It was a near thing, as the pilot said, the most anxious moment he had had in the “Gamma” during the manoeuvres. We then cruised round, looking for a more favourable spot. A narrow meadow, with high trees on three sides, offered the best shelter from the wind, and it was decided to attempt an entrance to it and land there. It was a delicate operation, requiring all the skill of both pilot and steersman; the last bag of ballast was thrown out just as she was coming to earth, and the propeller turned to lift her to save the bump. It was 5.20 am, but even at this early hour two men appeared and caught the landing rope, shortly followed by several more. Tying a ship down in the open is a difficult job, and the crew were kept busy for a time, putting in screw pickets, and securing ropes to them, their places in the ship being taken by the crowd that collected, the weight being necessary to replace the ballast and keep her on the ground.

We landed at a point 125 miles from Cambridge, and, with a little more east in the wind, would have just about hit the Bristol Channel. The experience had taught us a lot. It was somewhat chilly, we had no blankets, of course, and the freezing of the carburettor will give some idea of the temperature. However, we all felt fit and well at the end of it. The crew consisted of Major Maitland, pilot, who commands the airship squadron, Military Wing; Lieut. Osborne, R.N., Commanding Naval Wing; Naval Lieutenants Boothby and Fitzmaurice, wireless experts; Captain Brabazon, Irish Guards; Lieutenant Hetherington, 18th Hussars; Mr. Ryan, balloon expert in the Royal Aircraft Factory; Engineer Collins, and myself.

Side note: Access to search and read and download the Herald article and everything else via Trove is free. The Sphere cover was accessed via the British Newspaper Archive which is only free to search in a very rudimentary way. Reading actual pages is charged.